As any anthropologist or beauty historian will tell you, hair is never just hair. Throughout time and across the globe, cultures have used hairstyling to express tradition, art, and identity. Yet the hair culture of marginalized groups is all too often dismissed, derided, and discriminated against. This prejudice is especially true of Black hair, something that can severely impact self-image and mental well-being for children of color.

Fortunately, modern creators are providing young people with media that affirms and celebrates the beauty of Black hair. In her new picture book, Hairstory, Sope Martins reclaims a centuries-old history, artistry, and community, empowering children to take pride in their hair. We recently had the opportunity to chat with Sope about Hairstory, the fascinating origins of African hair culture, and the importance of providing literary access and representation to young readers.

Welcome to The Baby Bookworm, Sope! This is an incredibly powerful book. What inspired you to tackle the subject of Black hair culture and identity for young readers?

SM: A few things came together at the same time. My personal story of falling in love with my hair was the immediate spark. But I had also, for a long time, wanted to write about Africa’s long history of culture and excellence, which predates colonialism.

I had toyed with this in different forms, from alphabet concept books to fictional stories. When I began thinking seriously about writing about hair, those two interests finally met, and Hairstory came to be.

Hairstory does an incredible deep dive into the history of Black hair culture, tracing the roots of various styles and techniques to their roots in African society, tradition, and even folklore. Why do you think that having the context of this heritage can make an impact on young readers?

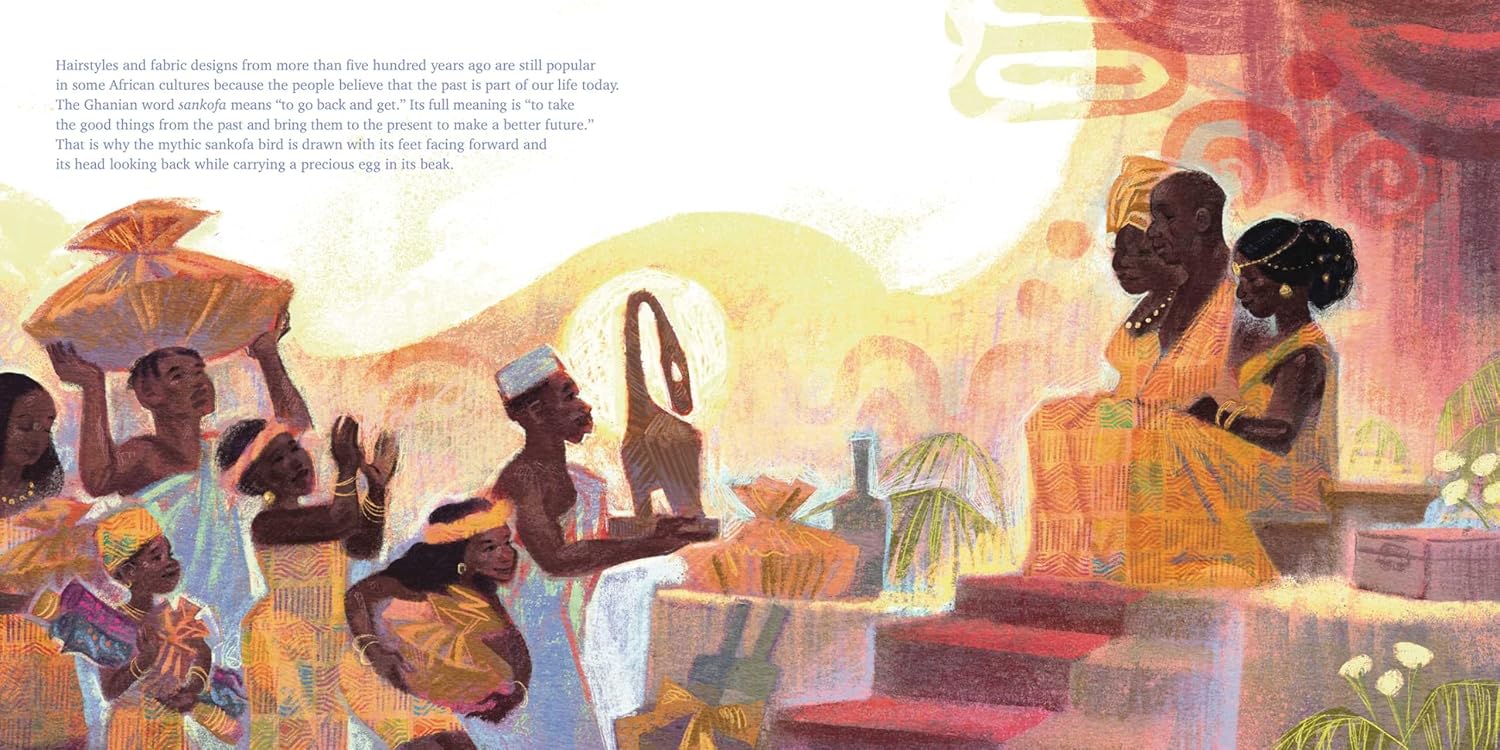

SM: Africa can often be presented as a monolith with few redeemable qualities in Western media. But Africa is a continent of many different countries, and within them, even more tribes. Each with their own rich history and culture.

When young readers discover the complex societies, philosophies, and creativity that can be uncovered even through something as everyday as hair, it challenges that narrative. This awareness can help reshape how they see themselves, their history, and their place in the world.

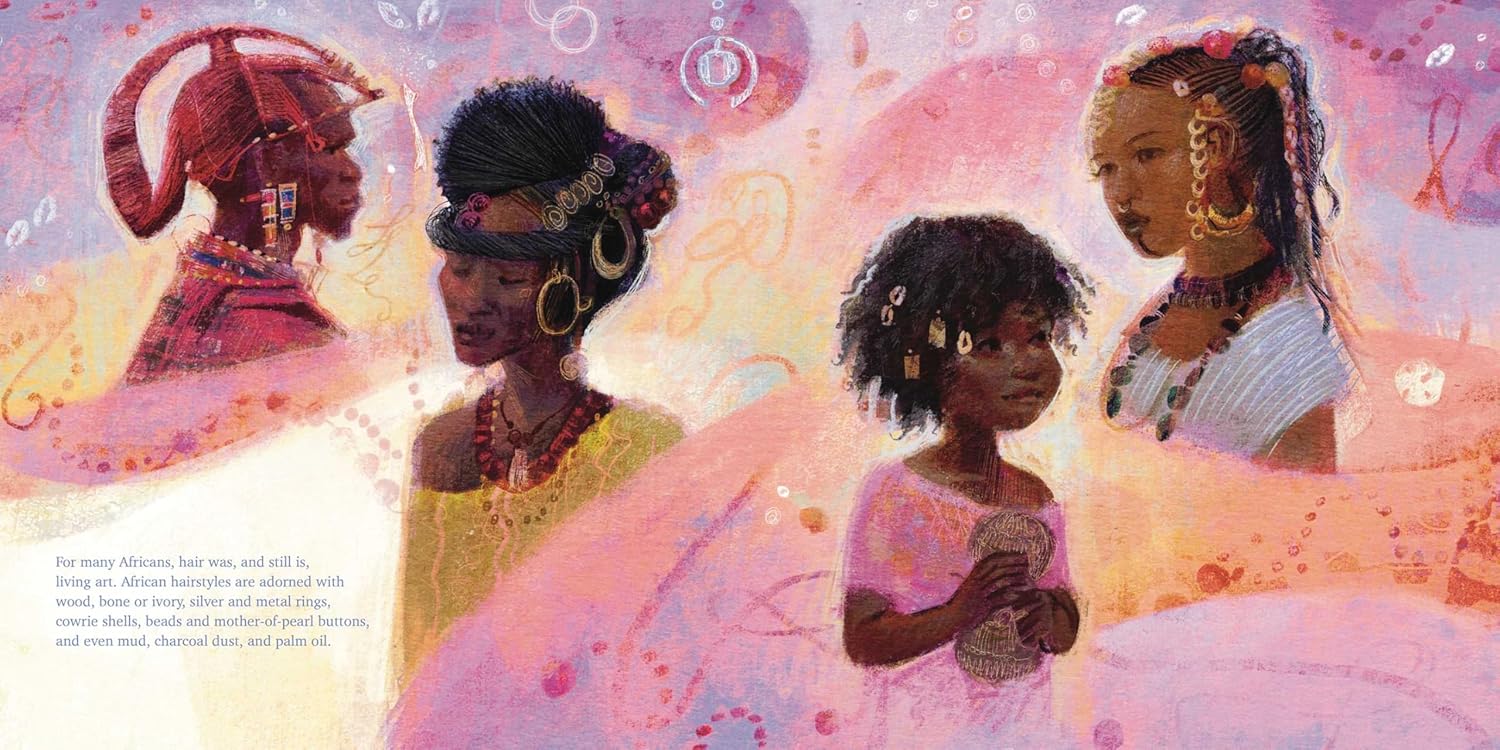

Your book also delves into the spiritual aspects of Black hair: in many cultures, certain styles and methods of care were—and still are—considered sacred. Do you feel such a connection to your own hair? If so, have you always felt this connection, or did it develop over time?

SM: I wouldn’t say I have a personal spiritual connection to my hair, but I do acknowledge and understand the value we place on it. I remember accidentally cutting off a large chunk of my hair a few years ago and weeping over it for days, which surprised even me.

I do find it fascinating how consistently hair carries some sort of spiritual meaning across cultures and belief systems. In Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Isese, hair is tied to different things, but it is important. I’m in awe of my hair, but then again, I am in awe of every part of the human body because we are walking miracles. And hair seems to be one of those places where that miracle becomes particularly visible to us.

Some of the lesser-known facts and history that you cover in Hairstory are absolutely fascinating. What was the research process like for this book?

SM: The research came in different stages. Once I decided to write Hairstory, my focus kicked in. We have something called the Reticular Activating System (RAS), which helps prevent our brains from getting overstimulated by directing our attention to what we deem important. It’s why you can hear your name in a crowded room. I mention this because the moment I decided to write a hair story, my brain started filtering in all these conversations about hair that had been happening around me.

I began listening more closely to people’s experiences, investigating local practices and histories, and actively asking people about their hair routines and beliefs. From there, I moved into more formal research. I read works like Emma Dabiri’s Twisted and Ayanna Byrd’s Hair Story, then followed the journal articles they referenced, which led me deeper and deeper down the research rabbit hole.

It was a genuinely fun process, even though I had to prune a lot of what I uncovered in the end. That’s the nature of research. I also created a research resource page on my website for anyone who wants to dig a little deeper.

Was there a piece of history or folklore that you learned in your research that particularly surprised you, or gave you a new perspective on African hair?

SM: Yes, and it came from my dual cultures. I am both Yoruba and Igbo, although I identify more strongly as Yoruba. In Yoruba belief, the earth we tread on is called Ilẹ̀, and it is often understood as a deity that is female in nature. In Igbo culture, Ala is the earth goddess. It was lovely to see this point of connection between my two cultural identities.

What would you say are the most common misconceptions about African hair and the culture that surrounds it, and why is it so important to dispel these misconceptions?

SM: There are so many misconceptions about African hair, such as:

- It doesn’t grow long

- It is coarse, unruly, and unrefined

- It isn’t neat, which makes natural hair unfit for school or work

- It is stronger than all the other hair types.

None of this is true, and challenging these misconceptions is important because it challenges the underlying assumptions and prejudices attached to them. By doing so, we’re changing the way children with this hair type see themselves.

I chose to focus on hair and history because Africa is a continent rich in history, culture, and enlightenment. Restoring that context restores pride.

Briana Mukodiri Uchendu’s artwork in Hairstory is positively stunning. Can you tell us a little bit about how it felt to see your writing realized in the book’s illustrations?

SM: Words fail me every time I talk about Briana’s art because, well, you’ve seen it. When Caitlyn Dhloughy told me she had found the perfect illustrator, I trusted her completely. Then I saw Briana’s work on The Talk, and it was the fastest yes I’ve ever sent via email. Birana’s illustrations tell their own story about hair, one that complements and elevates the text. Her visual storytelling was necessary for this book to exist in the world.

You are also the founder of The Kid Lit Foundation, which creates access to children’s literature and art education in Lagos and across sub-Saharan Africa. Can you tell our readers a little about the foundation and what inspired it?

SM: The genesis of The Kid Lit Foundation was in 2012 when I moved back to Nigeria. I experienced a kind of cultural shock in conversations about reading. While I spoke about stories and fiction, other people would talk about textbooks and self-help books instead. Reading for fun was a niche concept.

At the foundation, we work with children in their formative years, using stories across disciplines to activate imagination, empathy, and narrative thinking. Once a child can imagine a different world, they begin to believe this one can change, too.

By investing in story literacy, we’re helping raise the thinkers, creators, and leaders who will imagine and build Nigeria’s future. Through our mentorship programmes and literature festival, we also give children the agency to place their voices on a global platform.

What’s one piece of advice you would give to a young reader who is interested in bringing their own voice to the page, as you have done?

SM: Ask yourself what stories you love and why you love them. Ask what stories you wish existed. What book would you like to read that isn’t out there? If no one has written it yet, why not you? Your voice matters, and so do your stories.

Lastly, in honor of Hairstory, what is your favorite thing about your own hair?

SM: Oh, there are so many things I love about my hair! It is lush, thick, and it is wonderfully forgiving. I’ve put it through a lot over the years, but it keeps showing up for me, year after year.

About Sope Martins

Sope Martins is a Nigerian author of numerous children’s books, including The African Princess, Teju’s Shadow, and The Greatest Animal in the Jungle. She is also a radio broadcaster. Hairstory is her picture book debut in the United States.

An enormous thank you to Sope for taking the time to talk about her work with us. Be sure to check out her website at SopeMartins.com, and be sure to pick up a copy of Hairstory, on bookshelves now!